Certified Sustainable Diamond Jewelry

Where luxury meets responsibility

-

The highest level of sustainability assurance for diamonds

Pair your passion for brilliant diamonds with your care and respect for people and the planet. Certified Sustainability Rated Diamonds, whether lab-grown or mined, must meet rigorous sustainability requirements, backed by a science-based, multi-stakeholder standard, and then tracked at every step of the supply chain by an unbiased third-party. Look for authorized retailers that sell jewelry with Certified Sustainability Rated Diamonds.

-

Certification to verify a diamond’s traceability and sustainability

Certification is based on world’s first and most comprehensive sustainability standard for diamonds, SCS-007, developed by an international, multi-stakeholder committee, and applicable to both lab-grown and mined diamonds.

- Traceability

- Ethical stewardship

- Sustainable production

- Net zero carbon footprint

- Sustainability investments

-

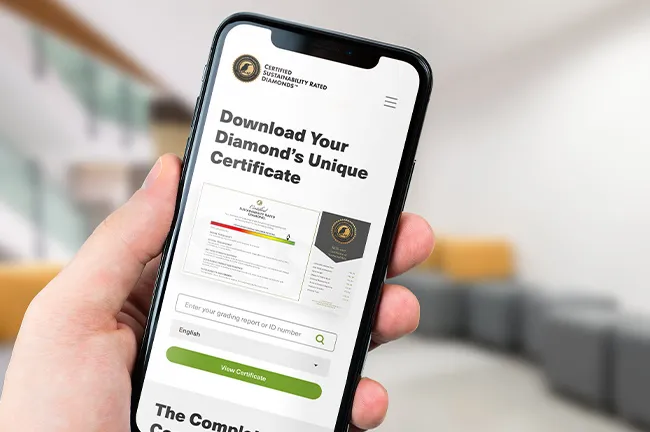

Each diamond comes with a unique Certificate of Sustainability

Every purchase of jewelry with an SCS Certified Sustainability Rated Diamond is accompanied by a digital certificate detailing the diamond’s ethical and environmental performance. This provides peace of mind that your diamond has been certified across all five pillars of sustainability.

The Five Pillars of Diamond Sustainability

News & Resources

Featured Retailers

Authorized Retailers of SCS Certified Sustainability Rated Diamonds